How a Pizza Order Sparked Nigeria’s Landmark ₦3 Million Data Privacy Victory

In March, when I reported that Eat N’ Go Ltd, the Nigerian master franchisee of Domino’s Pizza, had been ordered by a Federal High Court in Abuja to pay ₦3 million to a customer for privacy violations, the story sent shockwaves across Nigerian cyberspace.

The ruling exposed a knowledge gap that runs deep through the country’s digital ecosystem: most Nigerians—including many in the tech industry—remained unaware of just how sophisticated the Nigeria Data Protection Act was and how far the country had advanced in aligning its privacy framework with global best practices.

The public reaction told its own story. Comment threads filled with surprise that such enforcement was even possible in Nigeria. A few corporate executives reached out privately, suddenly concerned about their own data handling practices. Privacy advocates celebrated what many saw as a watershed moment.

But behind the headlines was a more personal story, one that began not with legal strategy or corporate malfeasance, but with a simple craving for pizza.

How it Started

The irony wasn’t lost on Chukwunweike Araka: a freshly minted lawyer, called to the Nigerian Bar only months earlier, was now poised to become the plaintiff in one of the country’s most consequential data privacy cases all because he ordered a pizza.

It was December 2023 when Araka’s phone first buzzed with an unexpected message from Domino’s Pizza.

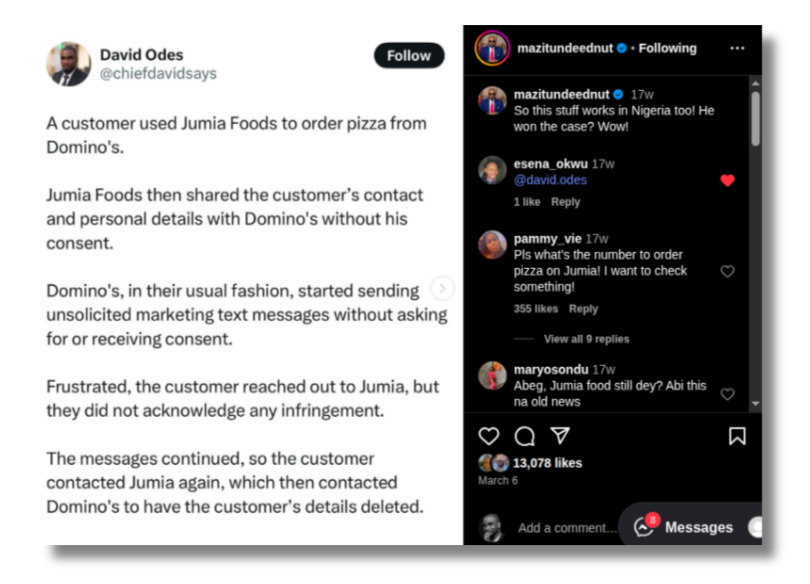

The promotional text began with “Hi, Jumians,” immediately catching his attention. He had never provided his contact details directly to Domino’s. The only connection was a food order he’d placed months earlier through Jumia Foods, Nigeria’s then-dominant food delivery platform.

“I was just irked. I was disgusted. I was angry at the message,” Araka told me during our recent conversation, his voice still carrying traces of the frustration he felt that December evening. “The fact that they were referring to me as a Jumian meant they got my personal data from Jumia, one way or the other.”

As someone who has spent some time documenting privacy violations across Nigeria’s digital ecosystem, what struck me about this case wasn’t just the violation itself—unsolicited marketing messages are endemic in Nigeria—but the methodical way Araka approached the problem.

Unlike most consumers who simply delete spam messages and move on, Araka understood both his rights under the newly enacted data protection law and the mechanisms available to enforce them.

“In view of the law that was passed that same year, the Nigerian Data Protection Act 2023, I knew that they were in the wrong automatically,” Araka explained. “That was wrongful marketing.”

The case that followed would test not just Nigeria’s nascent data protection framework, but also the willingness of its courts to hold major corporations accountable for privacy violations.

The Compliance Theatre

What emerges from court documents and my interview with Araka is a pattern of behaviour that privacy advocates know well: companies going through the motions of compliance while fundamentally misunderstanding their obligations under data protection law.

When Araka first complained to Jumia in January 2024, the company acted swiftly, contacting Domino’s to request that marketing messages cease.

Domino’s complied—temporarily. But two months later, the messages resumed with a new justification: Araka had placed another order, this time through Glovo, another food delivery platform.

“Their justification for the new round of marketing was that I initiated a new set of transactions with Glovo,” Araka said. “They felt like they were justified in using the personal data, that they had my consent more or less, but that’s not how the act works. The consent has to be explicit.”

The Legal Battle

When Domino’s refused Araka’s direct cease-and-desist letter and denied all liability, he sued.

The case, filed in July 2024 with support from Paradigm Initiative’s Ripoti Africa platform, sought ₦125 million in damages.

While Justice Emeka Nwite ultimately awarded far less—₦3 million—the precedent was set.

“Even after receiving my letter and acknowledging receipt of the letter, they still went ahead to market,” Araka told me, his frustration evident.

“The act says immediately a data subject objects, it should be prompt. It should be immediate. I’m saying stop using my data, you should stop it immediately.”

Domino’s defence in court was straightforward: they claimed consent. But as Justice Nwite noted in his judgment, “The question that must be asked is, was there a time the Applicant at any point consented to the use of his personal data for direct marketing messages? The answer is clearly No!”

A Broader Awakening

During our conversation, Araka was frank about the broader implications of his case. “I honestly believe that corporations need more wake-up calls. They need more cases,” he said.

“These guys usually have risk budgets. What’s one million naira to a bank like Polaris? They’d rather go to court and prove their point.”

Cases like these are significant because they reflect a quiet but meaningful shift in Nigeria’s regulatory landscape. Where companies once operated with little fear of accountability, rulings like this are beginning to reshape expectations both within boardrooms and among the public. Digital rights, long treated as theoretical, are finally being tested and upheld in court.

This creates opportunity for privacy advocates as each court victory not only sets precedent but helps educate consumers about their rights.

The ₦3 million judgment may be modest by international standards, but it represents something far more valuable: confirmation that Nigeria’s data protection laws have enforceable power.

The young lawyer who simply wanted his spam messages to stop has become an unlikely figure in the country’s growing digital rights movement.

For Nigeria’s digital economy, the case carries both promise and warning: the era of consequence-free privacy violations is drawing to a close.

As Araka told me: “The masses—that’s where the power is.”